War on Terro Why It Should Continue

All members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations

Article 2 (4) of the UN Charter

War, terrorism and human rights

Acts of war or terrorism challenge the human rights framework almost to the point where it seems to collapse. It is hard to see any place for human rights when human life is deliberately targeted, or where it is seen as "collateral damage" in the course of mass bombing campaigns, which either directly or indirectly lead to sickness, disease, suffering, destruction of homes, and death. In times of war, particularly wars which last for years on end, every human right appears to be affected adversely. Health systems break down, education suffers, and home, work, supplies of food and water, the legal system, freedom of the press and free speech, and accountability for abuses by the state – or by the "enemy" state – all see restrictions, if they do not disappear completely. However poor protections were in peacetime, the rights of children, women, minority groups and refugees will almost certainly be poorer still in times of war.

War and terrorism are indeed a breakdown of humanity, acts which seem to undermine and sideline the values at the heart of human rights – and the legal system which protects them. However, even in the midst of such a breakdown, human rights continue to operate, albeit in a weakened state, and although they cannot fix all evils, they can provide some minimal protection and some hope for justice.

Wars and national emergencies allow for states to "derogate" from – or temporarily put aside – some of their human rights commitments. However, certain human rights, such as the right to life or the right to be free from torture, inhuman and degrading treatment can never be put aside. These are regarded as so important and so fundamental that they should be observed even when a state's security is at risk.

A judgment of the European Court of Human Rights in 20113 (Al-Skeini and Others v. the UK) found that the United Kingdom had been in violation of Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights, providing for the right to life, in its treatment of a number of civilians while carrying out security operations in Basra, Iraq. The case was the first of its kind in finding that the European Convention applied in times of war, in foreign territories, and over the whole region for which a signatory to the Convention had effective control. Other cases have found that the treatment given to prisoners in detention camps amounted to torture.

When is a war a war?

In many ways war and terrorism are very similar. Both involve acts of extreme violence, both are motivated by political, ideological or strategic ends, and both are inflicted by one group of individuals against another. The consequences of each are terrible for members of the population – whether intended or not. War tends to be more widespread and the destruction is likely to be more devastating because a war is often waged by states with armies and huge arsenals of weapons at their disposal. Terrorist groups rarely have the professional or financial resources possessed by states.

Apart from the methods used and the extent of the violence, however, war and terrorism are also seen differently by international law. The differences are not always clear-cut and even experts may disagree about whether a violent campaign counts as terrorism, civil war, insurgency, self-defence, legitimate self-determination, or something else.

Question: In the 20th century, Chechens, Abkhaz, Kurds, Palestinians and Irish Nationalists have all seen themselves as fighting a war against a colonising nation. Nation states have always regarded the actions of such groups as terrorism. How can we decide which is the right term?

Problems in defining war

Wars are sometimes defined by the fact that they take place between nation states: but where does that leave civil war, or the so-called "War on Terrorism"? Sometimes a formal declaration of war is taken as defining an act of war, but that excludes low-level bombing campaigns which take place over a number of years, such as the United States' attacks on the borders of Pakistan or in the no-fly zones declared over Iraq in the 1990s.

Should a definition of war include economic or trade wars, both of which may be enormously destructive in terms of human life? Are sanctions a form of war? UNICEF estimated that the sanctions on Iraq in the 1990s led to the deaths of over half a million children (and many adults).

Question: Carl Von Clausewitz, a Prussian military general, defined war as follows: "War is thus an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will." Do you agree with this as a definition?

What is terrorism?

Terrorism is another of those terms that everyone seems ready to use, but no-one can agree on an exact definition. Even the experts continue to argue about the way the term should be applied, and there are said to be over a hundred different definitions of terrorism, not one of which is universally accepted.

This lack of agreement has very practical consequences: to take just one example, the UN has been unable to adopt a convention against terrorism, despite trying for over 60 years to do so, because its member states cannot agree on how to define the term. The UN General Assembly tends to use the following in its pronouncements on terrorism:

"Criminal acts intended or calculated to provoke a state of terror in the general public, a group of persons or particular persons for political purposes are in any circumstance unjustifiable, whatever the considerations of a political, philosophical, ideological, racial, ethnic, religious or any other nature that may be invoked to justify them."5

Ancient Terrorists

The three most famous "terrorist" groups existing before the 18th century were religiously inspired, (and all had names which passed into the English language as words associated with their acts: fanatics are known as zealots, assassins are murderers, and thugs are violent or brutish individuals).

- The Sicarii, otherwise known as the Zealots, were a Jewish movement in the 1st century who tried to expel the Romans from Palestine. They used ruthless methods, including mingling in crowds at public gatherings and stabbing their victim before disappearing back into the crowd.

- The Assassins were a medieval Shia Muslim sect who aimed to purify Islam, and targeted prominent religious leaders, using similar methods to the Sicarii in order to gain publicity.

- The Thugi (Thuggee) were an Indian group sometimes classified as a cult or sect, which operated over the course of about 600 years, brutally murdering travellers by strangulation, and according to very specific rules. They are the longest lasting such group, and were eliminated in the 19th century largely as a result of recruiting informants from within the group.

Question: Should the threat to use a nuclear bomb be classed as terrorism?

Terrorism: a classification

Some of the following criteria have been seen as important in deciding whether an act is one of "terrorism". Be aware that the experts do not all agree!

- The act is politically inspired

An act of terrorism normally has an end goal which is "bigger", and more strategic than

the immediate effect of the act. For example, a bomb attack on civilians is meant to

change public opinion in order to put pressure on the government.

- The act must involve violence or the threat of violence.

Some think that the mere threat of violence, if genuinely believed, may also be an act of

terrorism, because it causes fear among those at whom it is directed, and can be used for political ends.

- An act of terrorism is designed to have a strong psychological impact.

Terrorist acts are often said to be arbitrary or random in nature, but in fact groups tend to select targets carefully in order to provoke the maximum reaction, and also, where

possible, to strike at symbols of the regime.

- Terrorism is the act of sub-state groups, not states.

This is probably the most widely disputed among different observers and experts. Nation states tend to use this as the essence of a terrorist act, but if we limit terrorist acts to sub-state groups, then we have already decided that a violent act carried out by a state cannot be terrorism, however terrible it may be!

- Terrorism involves deliberately targeting civilians.

This criterion is also disputed by many experts, since it rules out the possibility of attacks against military personnel or other state officials such as politicians or the police being classified as terrorist attacks.

Question: Can you define terrorism? How would you distinguish acts of terrorism from other forms of violence?

Can states commit terrorism?

The word terrorism was first used to describe the "Regime de la Terreur" (the Reign of Terror) in France in the last decade of the 18th century, and in particular, the period from 1793-1794 under Maximilien Robespierre. These years were characterised by the use of violent methods of repression, including mass executions authorised by the Revolutionary Tribunal, a court set up to try political offenders. Towards the end of this era in particular, people were often sentenced only on the basis of suspicion and without any pretence at a fair trial.

All of the above led to a general atmosphere of fear: a state in which people could no longer feel secure from the threat of arbitrary violence. From such beginnings, the concept of terrorism entered the vocabulary.

During the 19th century, the term terrorism came to be associated more with groups working within a state to overthrow it, and less with systems of state terror. Revolutionary groups throughout Europe often resorted to violence in order to overthrow rulers or state structures that they saw as repressive or unjust. The most favoured technique was generally assassination and among the "successes" were the assassination of a Russian tsar, a French president, an Austro-Hungarian empress and an Italian king.

The 20th century, the most terrible in terms both of numbers of victims and perhaps in terms of the cruelty and inhumanity of methods, saw both governments and sub-state groups turning to violence in pursuit of their goals. The actors and initiators in this series of horrible dramas have included state officials, as well as sub-state groups. However, by the end of the century, it was almost exclusively the latter that were termed terrorist groups. The sub-state groups are often armed, funded and even trained by other states: does that make the states which prepare and support these groups terrorist states?

Question: Do you think state actions should be termed "terrorist" actions if they cause terror in the population?

The use of force in international law

International law covers a number of different cases involving the use of force by states. Sometimes – as in the quote at the start of the chapter – the law applies to cases when one state uses or threatens force against another state. Such cases are normally classed as wars, and are regulated by the UN Charter and the Security Council. Sometimes the law applies to the way force is used in the course of war – whether legal or illegal. This is generally the area of international humanitarian law. Even while a war is taking place, however, human rights law continues to function, although for certain rights, restrictions by the state may be more permissible than they would be in peace time.

War in international law

UN Charter, Kellogg-Briand Treaty

The High Contracting Parties solemnly declare in the names of their respective peoples that they condemn recourse to war for the solution of international controversies, and renounce it, as an instrument of national policy in their relations with one another.

From the Kellogg-Briand Pact

(also known as the General Treaty for the Renunciation of War, or the Pact of Paris)

As the most grandiose act in a series of peacekeeping efforts after the First World War , the Kellogg-Briand Pact was signed by 15 states in 1928, and later on by 47 others. Although the Treaty did not prevent later military actions between signatories, nor the eruption of the Second World War, it was important because it established a basis for the idea of "crimes against peace" and thus played a central role at the Nuremberg Trials. According to the Nuremberg (or Nürnberg) Principles6, crimes against peace include the "planning, preparation, initiation, or waging of wars of aggression, or a war in violation of international treaties".

After the Nuremberg Trials, the Charter of the United Nations became the key international treaty regulating member states' use of force against each other. The Charter does not forbid war completely: it allows, in certain tightly defined circumstances, states to engage in war where this is necessary for them to defend themselves. Even such wars of self-defence, however, must be approved by the UN Security Council, except in rare cases where immediate action is necessary and there is insufficient time for the Security Council to meet.

Responsibility to protect (R2P)

In recent years, some countries have pushed for the idea that where people are suffering grave abuses at the hands of a state – for example, genocide is threatened – the UN should have the power, and the obligation, to step in to protect the people. This has included the possibility of military action against the state responsible. The genocide in Rwanda, where the international community failed to intervene, sparked the debate. The war in Kosovo was seen as one of the first examples of "humanitarian intervention" by military means and in 2011, NATO's military intervention in Libya was based on a similar principle.

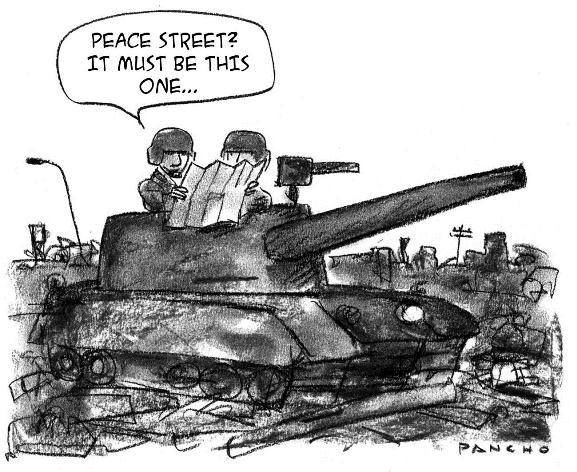

The idea of R2P is not uncontroversial. Genocide and the other acts included are serious and terrible acts. However, critics have argued that R2P may be used as a pretext and some military interventions have not really been based on the likelihood of "mass atrocity crimes" but have been more political in nature. Many mass atrocity crimes do not appear to evoke R2P, and some of those where intervention has taken place have seemed less serious in terms of the dangers people face. Even the Responsibility to Protect involves the idea that intervening states should explore all other possible means before undertaking military action. It is not always clear that these avenues have been explored. Finally, people have questioned whether war, which is itself a terrible and destructive act, is an appropriate means of putting an end to suffering. Can the bombing of a country, with all that it entails, be the best way to promote peace and resolve what is often a much more deep-seated conflict between two sides?

Question: Can war be the "best of two evils"?

The laws of war

Even in times of war, there are certain laws which impose limits on the actions of the warring parties, for example, concerning the treatment of prisoners of war, targeting civilian populations and medical care for the wounded. The "laws of warfare" are mostly governed by international humanitarian law, otherwise known as the Geneva Conventions.

The first Geneva Convention

The first of the Geneva Conventions was signed in 1864. It was created after Henry Dunant, a citizen of Geneva, witnessed a ferocious battle at Solferino in Italy in 1859. He was appalled by the lack of help for the wounded, who were left to die on the battlefield, and proposed an international treaty which would recognise a neutral agency to provide humanitarian aid in times of war. His proposals led to what later became the creation of the International Committee of the Red Cross and also to the first Geneva Convention. The Convention made provisions for the humane and dignified treatment of those no longer engaged in the battle, regardless of whose side they were on.

The Geneva Conventions continued to be developed up to 1949, when the fourth Geneva Convention was adopted and the previous three were revised and expanded. Later, three amendment protocols were added. These Conventions have been ratified in whole or in part by 194 countries.

In addition to the Geneva Conventions, there are other standards in international humanitarian law, including the Hague Conventions and a range of international treaties on the weapons that can and cannot be used in warfare. Throughout the 1990s, a coalition of NGOs successfully lobbied for an international ban on the production and use of landmines. The Ottawa Treaty or the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention was adopted in 1997 and has since been ratified by 157 states worldwide. The Coalition continues to campaign for a treaty which bans the use of cluster bombs, which, just like landmines, leave a trail of destruction even once a war has ended.

War crimes

The most serious violations of international humanitarian law are considered to be war crimes. War crimes are such serious offences that they are held to be criminal acts for which individuals can be held accountable.

War crimes

Based on the Fourth Geneva Convention (1949), war crimes (in the Convention: "grave breaches") include:

"Wilful killing, torture or inhuman treatment, including biological experiments, wilfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health, unlawful deportation or transfer or unlawful confinement of a protected person, compelling a protected person to serve in the forces of a hostile power, or wilfully depriving a protected person of the rights of fair and regular trial [...], taking of hostages and extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly."9

Other acts for which individuals can be held responsible include crimes against humanity, mass murder and genocide. Crimes against humanity are severe crimes committed against a civilian population, such as murder, rape, torture, enslavement and deportation.

The first trials of individuals for such crimes were the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials of Nazi and Japanese political and military leaders in the aftermath of the Second World War. Since then, a number of ad hoc tribunals have been set up, for example to deal with the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Cambodia, Lebanon and Sierra Leone. Other conflicts, many equally serious, have not seen special tribunals set up, which has sometimes provoked criticism that the decision on whether to do so is influenced by political factors.

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was set up by the UN to prosecute serious crimes committed during the wars in the former Yugoslavia and to try their perpetrators. The majority of those indicted have been Serbs and this has led to accusations of bias from some observers. Both Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch criticised the ICTY for failing to investigate a number of serious charges against the NATO forces, including the bombing of Serbian State Television and a railway bridge when it was evident that civilians had been struck. Amnesty's report into violations of humanitarian law recorded that "NATO failed to take necessary precautions to minimize civilian casualties".10

Question: War Tribunals – including the Nuremberg Trials – are sometimes seen as "victor's justice". Do you think both sides in a war should be judged according to the same principles?

The International Criminal Court

The second half of the 20th century saw a movement to set up a permanent court to deal with the worst crimes against humanity. In 1998, the Rome Statute was adopted, which provided the legal basis for the creation of the International Criminal Court (ICC). The ICC came into being in July 2002 and sits in The Hague in the Netherlands.

The ICC is the first permanent international court and has been set up to prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide and the crime of aggression. Even though the Rome Statute is ratified by states, the ICC prosecutes individuals who are responsible for crimes, not the states. As of 1 January 2012, 119 countries are state parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, including nearly all of Europe, but excluding for example the United States, India, China and Russia. The court has opened investigations into conflicts in Sudan, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, the Central African Republic and Libya.

Question: Can you think of any individuals who are responsible for war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide or the crime of aggression that should be taken before the International Criminal Court?

Terrorism in international law

Drawing up international legislation to deal with terrorism has been beset with problems, mainly because of the difficulty of reaching a common definition of the term. The Council of Europe has produced a set of guidelines12 on where the line can be drawn in order not to violate other international treaties or agreements.

The guidelines contain the following key points:

- Respect for human rights and the rule of law – and prohibition of discrimination.

- Absolute prohibition of torture: "The use of torture or of inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, is absolutely prohibited, in all circumstances …"

- The collection and processing of personal data must be lawful and proportionate to the stated aim.

- Measures which interfere with privacy must be provided for by law.

- Anyone suspected of terrorist activities may only be arrested if there are reasonable suspicions and he/she must be informed of those reasons.

- A person suspected of terrorist activities has the right to a fair hearing, within a reasonable time, by an independent, impartial tribunal established by law. They benefit from the presumption of innocence.

- "A person deprived of his/her liberty for terrorist activities must in all circumstances be treated with due respect for human dignity."

- "The extradition of a person to a country where he/she risks being sentenced to the death penalty or risks being subjected to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment may not be granted."

- "States may never […] derogate from the right to life as guaranteed by these international instruments, from the prohibition against torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, from the principle of legality of sentences and of measures, nor from the ban on the retrospective effect of criminal law."

Human rights and terrorism

There are two key areas where the concepts of human rights and terrorism may come into conflict: the first, most obviously, concerns an act of terrorism itself; the second concerns measures that may be taken by official organs in the process of trying to counter terrorism.

Irrespective of the way that terrorism is defined and irrespective of the reasons behind it or the motivation for engaging in it, the act of terrorising members of the population constitutes a violation of their dignity and right to personal security, in the best case, and a violation of the right to life, in the worst. In terms of human rights law, the matter is less simple since human rights law has mostly been drawn up to protect individuals from infringements on their rights and liberty from the side of governments. There is no possibility, for example, to take a terrorist group to the European Court of Human Rights!

However, governments do possess certain obligations: firstly, in terms of protecting citizens from attacks on their personal security; secondly, in terms of compensating victims who may have suffered from terrorist attacks; and thirdly, of course, in terms of not engaging in terrorism themselves.

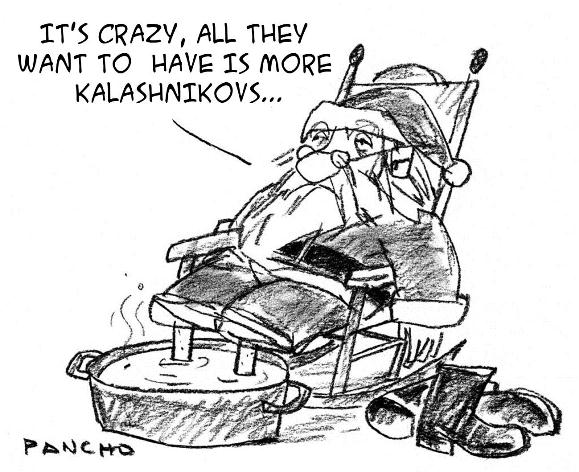

Question: Do you think that a country which exports arms which are then used against civilians should be held accountable for the use to which the weapons are put? Do you know which groups or countries your government sells arms to?

A number of human rights issues arise in connection with the fight against terrorism – and there is almost bound to be a continuing tension between the measures a government regards as necessary to take in order to protect the populace and the rights it may need to limit in order to do so.

Secret renditions

A report written by Dick Marty for the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in 200613 looked at the assistance given by various European countries to the United States of America in "rendering" suspected terrorists to countries where they faced torture. The report found that 7 countries – Sweden, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Britain, Italy, Macedonia, Germany and Turkey – could be held responsible for "violations of the rights of specific persons" because they had knowingly assisted in a programme which resulted in individuals being held without trial, often for a number of years and being subjected to torture. Other countries, including Spain, Cyprus, Ireland, Greece, Portugal, Romania and Poland were also accused of "collusion" with the United States. Marty said he had evidence to show that Romania and Poland were detainee drop-off points near to secret detention centres.

The victims of conflict

War and terrorism have a terrible and long-lasting impact on huge numbers of people. Deaths at the time of conflict are just one element: psychological trauma, collapse of the physical and economic infrastructure, displacement of people, injury, disease, lack of food, water or energy supplies and a breakdown of trust and normal human relations are some of the others. The impact can last for generations.

With the decline in inter-state wars and the rise in civil wars and new methods of warfare, civilian populations are now at more risk and suffer higher casualties than professional soldiers. UN Women estimate that in contemporary conflicts as many as 90% of casualties are civilians, the majority of whom are women and children14. Rape and sexual violence are used as a weapon of war, as a tactic to humiliate, dominate and instil fear in communities.

Women in armed conflicts

In October 2000, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1325 to address the issues faced by women in armed conflict. The Resolution calls for their participation at all levels of decision making on conflict resolution and peace building. Four further resolutions have since been adopted by the Security Council. The five documents focus on three key goals:

- Strengthening women's participation in decision making

- Ending sexual violence and impunity

- Providing an accountability system

Child soldiers

A particularly sobering development in warfare, particularly over the past ten years, is the use of children as soldiers in brutal conflicts. Child soldiers exist in all regions of the world and participate in most conflicts. However, the problem is especially critical in Africa, where children as young as nine have taken part in armed conflict. Most child soldiers are between the ages of 14 and 18. Child soldiers are recruited by both rebel groups and government forces.

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child requires state parties to ensure that children under the age of 15 do not take part in hostilities. However, this is felt by many to be too low, and initiatives have been made to raise the minimum to 18 years old. The Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict (with 143 state parties as of November 2011) raised the minimum age to 18.

European countries do not recruit under the age of 17 and do not send soldiers into combat under the age of 18. The UK has the lowest recruitment age in Europe – 16 years old, although this is nominally for training purposes only. The UK has been widely criticised for this by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. In Chechnya, children under 18 have reportedly served in rebel forces.

Youth, war and terrorism

Young people are directly concerned by war in many ways. In addition to the case of child soldiers mentioned above, young people constitute the vast majority of soldiers, especially in countries and times of national military service. It can therefore be said that young people are in the front line of the victims of war. In the case of professionalised armies, it is often young people from underprivileged social backgrounds who are enlisted into armed forces, because they have fewer opportunities of earning a decent living.

Young people are often targeted by terrorist groups as possible agents of terrorist attacks, regardless of the motivation, as exemplified by the attacks in London in 2005. This is often attributed to the identity-searching that some young people experience and that makes them especially vulnerable to extremist ideas and ideals. Young people may also be specifically targeted by terrorist attacks, as exemplified by the attacks in Norway in 2011 and by attacks on schools in the Caucasus.

Youth organisations have traditionally played an important role in raising awareness about the non-sense of war and the costs it imposes on young people. Several reconciliation and exchange programmes were set up after the carnages of the First World War; many of them still exist today, such as Service Civil International or the Christian Movement for Peace / Youth Action for Peace which promote international voluntary youth projects and workcamps.

The European Bureau of Conscience Objection works for the recognition of the right to conscience objection to military service – the right to refuse to kill – in Europe and beyond.

War Resisters International is an international movement created in 1921 under the credo: "War is a crime against humanity. I am therefore determined not to support any kind of war, and to strive for the removal of all causes of war". WRI promotes non-violence and reconciliation and supports conscience objectors and asylum seekers in cases of draft evasion or desertion.

Endnotes

1 Bob Marley in the song "War", adapted from Ethiopian Emperor H.I.M. Haile Selassie's address to the United Nations on October 1963

2 Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice of 9 July 2004, para. 106.

3 Al-Skeini and Others v. the United Kingdom, European Court of Human Rights Grand Chamber (Application no. 55721/07), 7 July 2011; http://www.bailii.org/eu/cases/ECHR/2011/1093.html

4 Jeanette Rankin was the first woman to enter U.S. House of Representative in 1917

5 1994 United Nations Declaration on Measures to Eliminate International Terrorism annex to UN General Assembly resolution 49/60 , "Measures to Eliminate International Terrorism", of December 9, 1994

6 Document A/CN.4/L.2, Text of the Nürnberg Principles Adopted by the International Law Commission, Extract from the Yearbook of the International Law Commission: 1950,vol. II; http://untreaty.un.org/ilc/documentation/english/a_cn4_l2.pdf

7 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide; http://www.un.org/millennium/law/iv-1.htm

8 http://www.physiciansforhumanrights.org/blog/us-ban-landmines-facts.html

9 Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949 http://www.icrc.org/ihl.nsf/FULL/380?OpenDocument

10 NATO/Federal Republic of Yugoslavia "Collateral Damage" or Unlawful Killings? Violations of the Laws of War by NATO during Operation Allied Force, Amnesty International - Report - EUR 70/18/00, June 2000; http://www.grip.org/bdg/g1802.html

11 See Endnote 2 above

12 Human rights and the fight against terrorism, The Council of Europe Guidelines, 2005; http://www.echr.coe.int/NR/rdonlyres/176C046F-C0E6-423C-A039-F66D90CC6031/0/LignesDirectrices_EN.pdf

13 Alleged secret detentions and unlawful inter-state transfers involving Council of Europe member states, Parliamentary Assembly, Doc. 10957, 12 June 2006 http://assembly.coe.int/Documents/WorkingDocs/doc06/edoc10957.pdf

14 http://www.womenwarpeace.org/

whitemanuntes1960.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.coe.int/en/web/compass/war-and-terrorism

Belum ada Komentar untuk "War on Terro Why It Should Continue"

Posting Komentar